CONVEX MIRROR

Intimacy & extimacy

Every European music listener has probably experienced once the medieval gothic cathedral as a space at some point, as an overwhelming experience.

The expanse, height and spatial sound as a physical sensation may perhaps be compared to the starry sky that we all are allowed to contemplate on moonless nights. A kind of insatiable wonder appears within us.

The distance resembles the apparent distance to God, the Great Consciousness.

And yet we may be overcome, at the same time, by a feeling of intimacy, of a familiar infinity that is perhaps also revealed in our own intimacy. Time and time again, we recognise ourself when waking up in the morning. An infinite neverending intimacy.

The oversized space of the house of God, the sky of stars, becomes a protective and at the same time permeable membrane, where intimacy with ourselves or with God, with the miracle of life, with the great unity of all being finds its place, protected as in a chamber where prayer or meditation is practiced before going to sleep or after.

Intimacy in the midst of extimacy.

Extimacy despite intimacy.

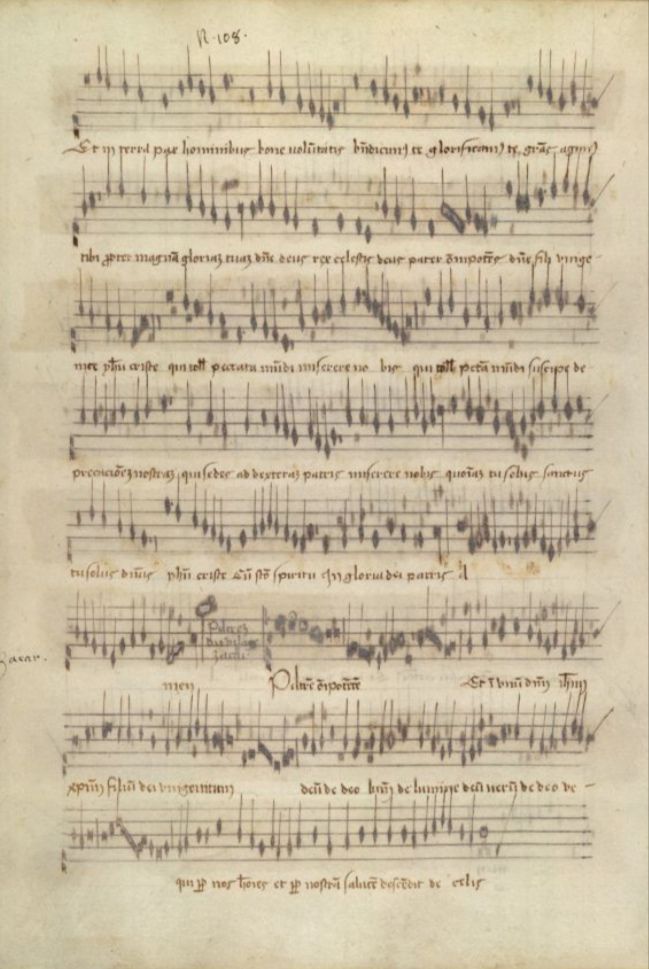

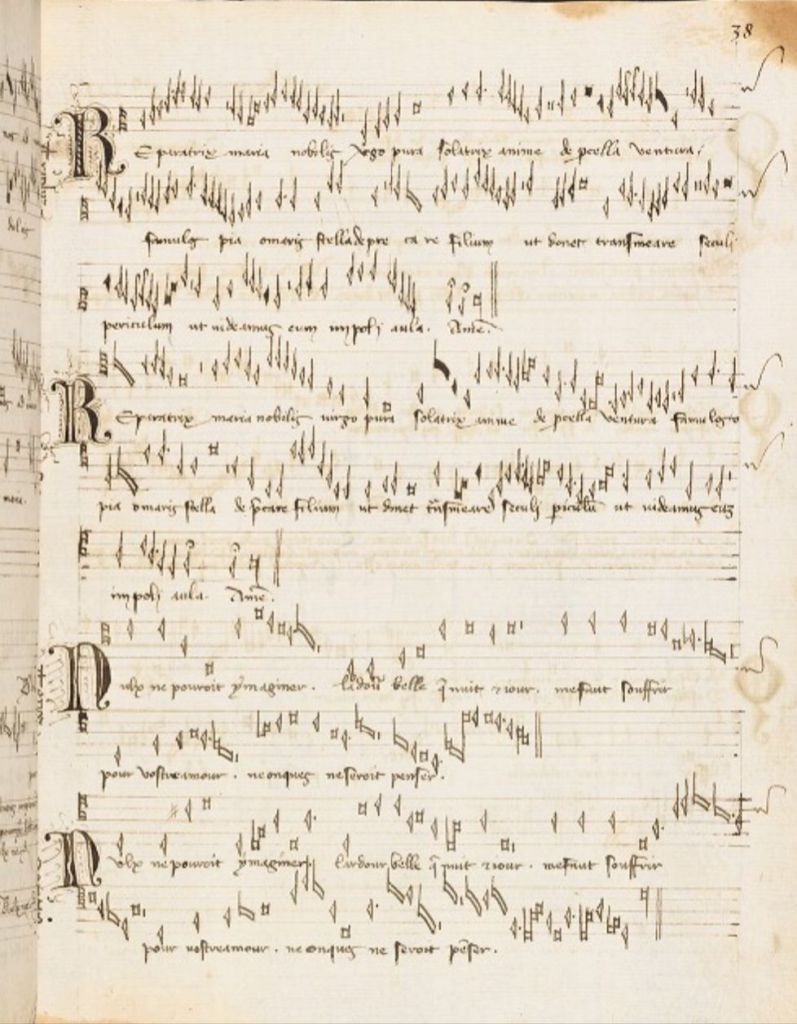

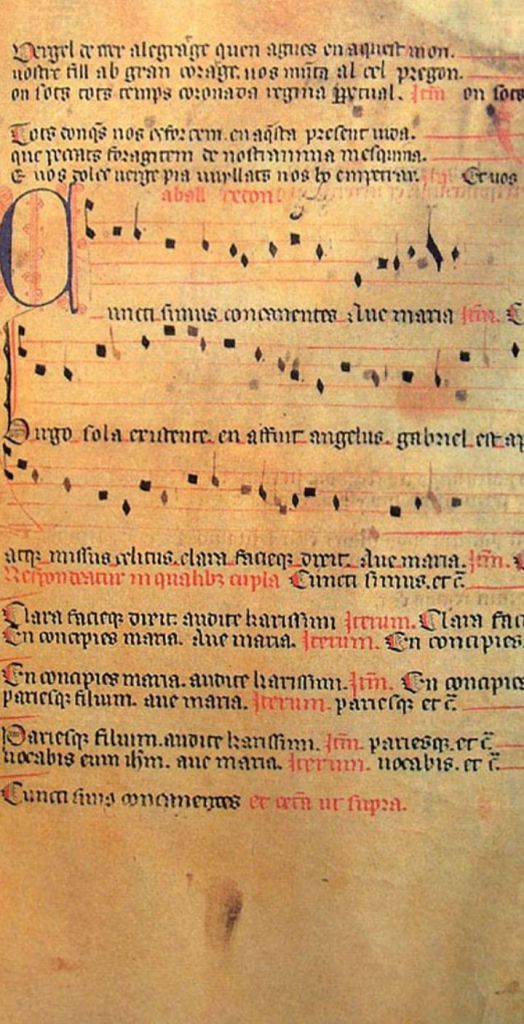

However, the ‘time of the cathedrals’ is also the time of intimate chambers where chanson and love lyrics resound.

Whether it is mundane love or religious love that is offered, it is not separated by the four narrow walls.

The window allows a view out into the starry sky. Into the universe.

Into the infinite expanse, size, height and inseparable wholeness.

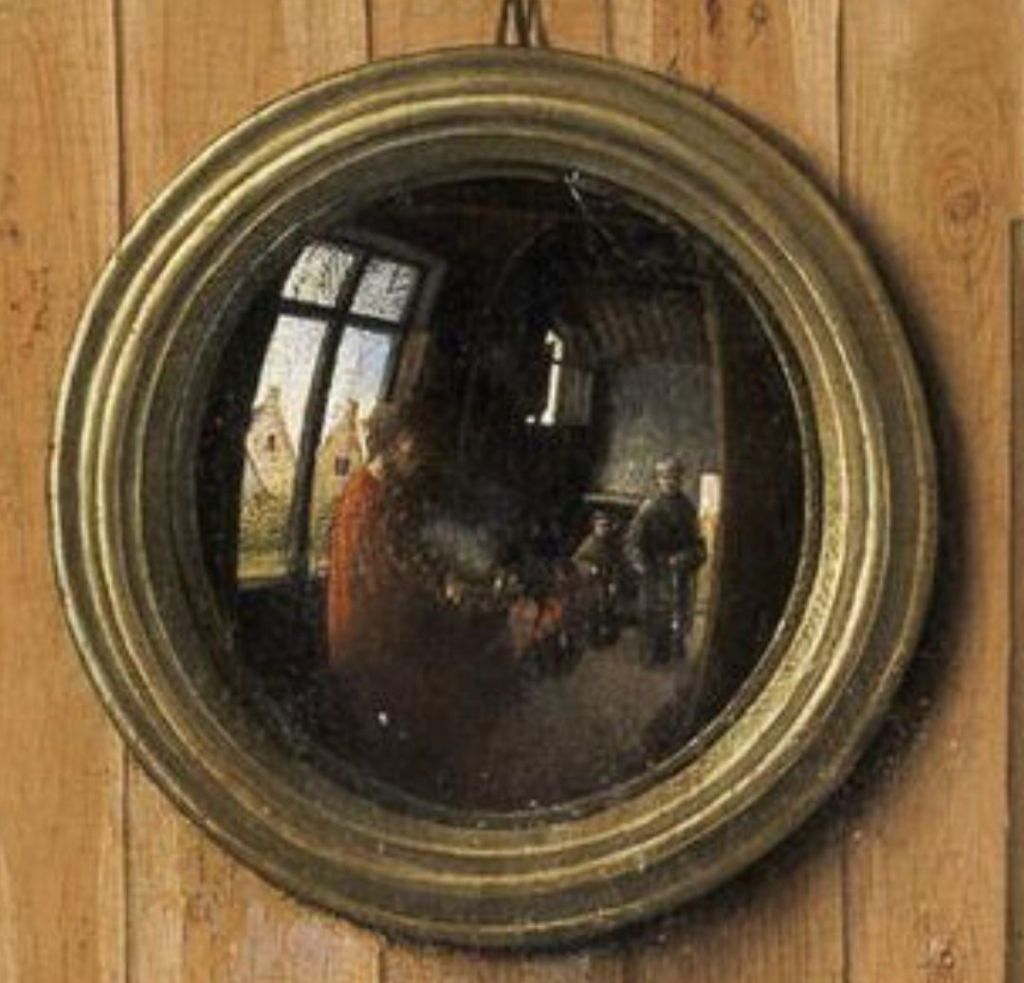

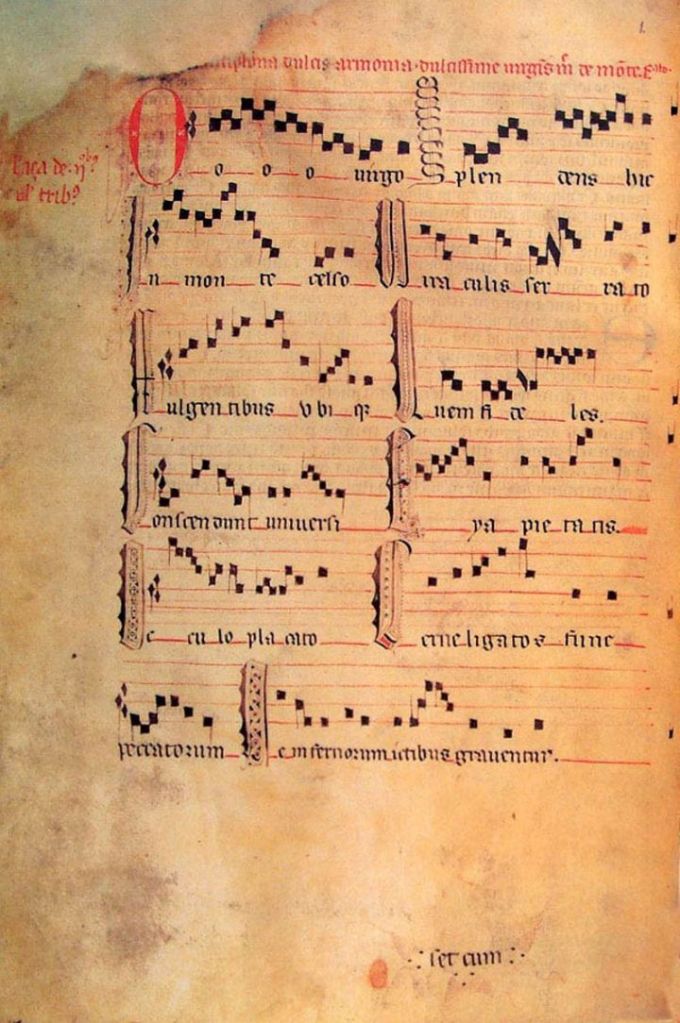

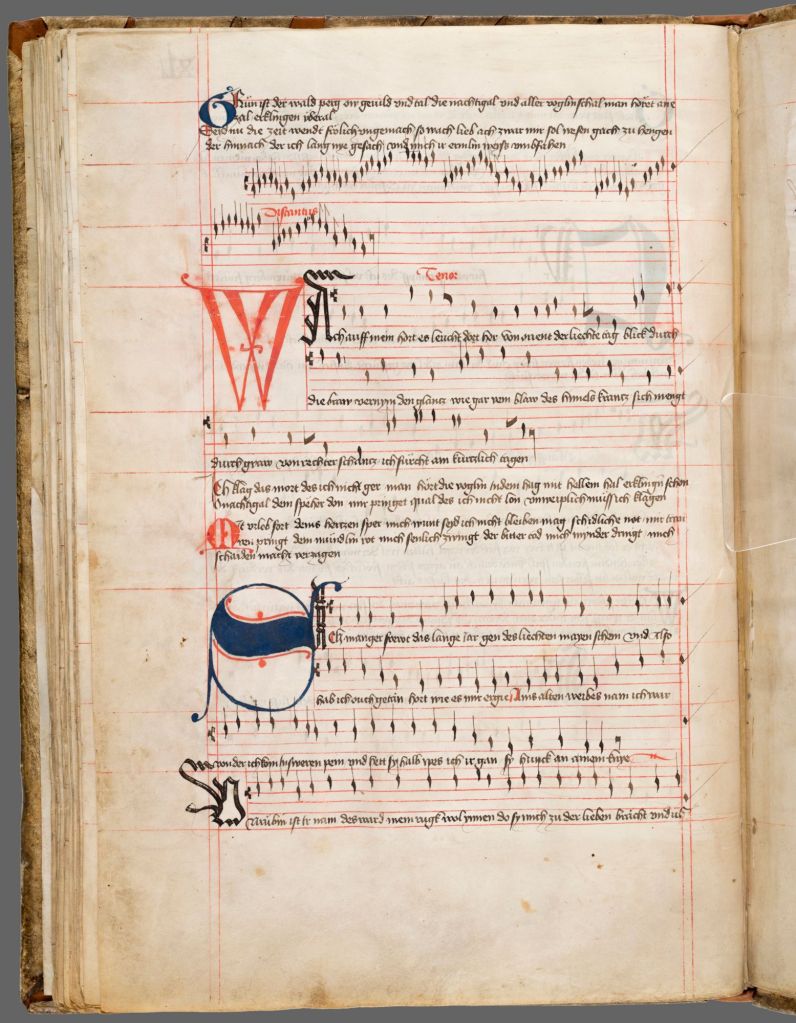

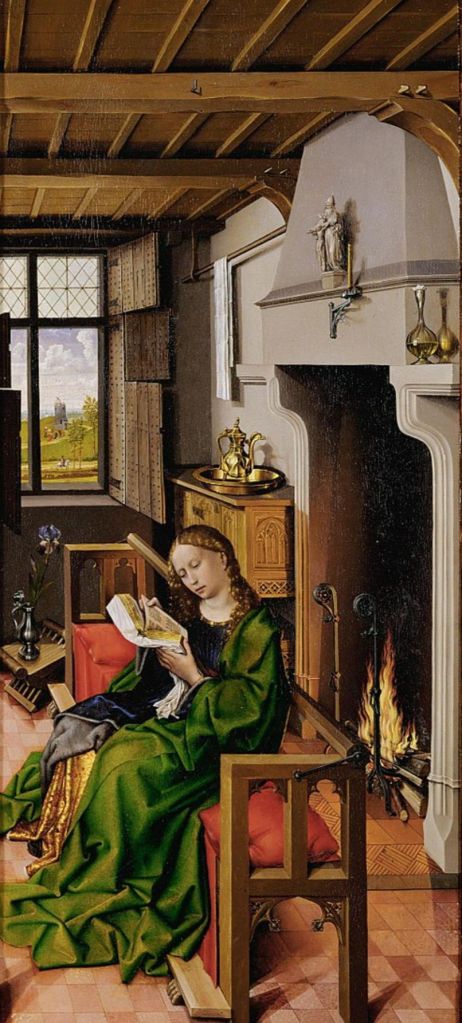

The Convex Mirror, which can be recognised in Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Wedding Painting 1434 and in Robert Campin’s Triptych of Cologne’s Heinrich von Werl, allows the narrow space to be seen in its entirety. The incredible accuracy in perspective and detail are probably due to an achievement of the science of optics, the mirror lens. If you compare Campin’s paintings with the refined draperies, the photo-like portraits, or the chandelier in van Eyck’s convex mirror with Giotto’s paintings from around 1310, you immediately realise that a technical achievement is making way for new spaces. Are they more intimate spaces? Are they achievements or merely spaces that allow us to experience things differently?

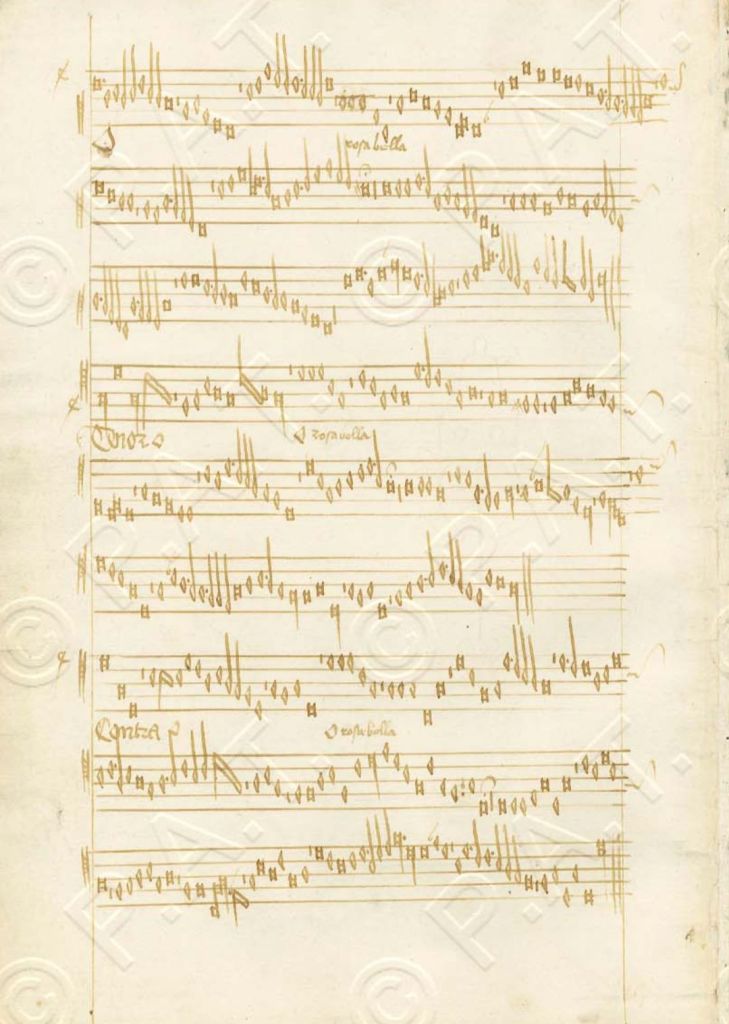

Perhaps something similar happens in music. The Convex Mirror opens up more detailed listening. Perhaps more intimate listening? Writing becomes more virtuosic, like the draperies of Campin and others at the beginning of the 15th century.

A mantra of light, the convex mirror, which reflects the unheard-of vastness of the music of the extimacy of Cathedrals, and the intimacy, the closeness of the chanson, not as a contrast but as «an inseparable whole».

The music here perhaps becomes a ‘Space as a Membrane’: sonic ‘Klangrausch’ like the enumeration of a hundred saints in a litany, or the poetic epic world of subtlety, the chanson.

Separate and yet permeable.

Intimacy versus extimacy.

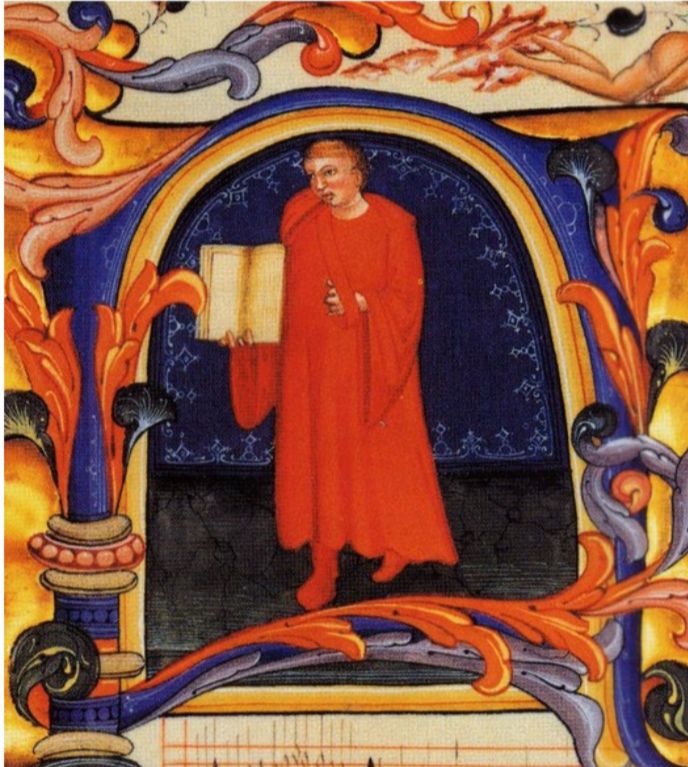

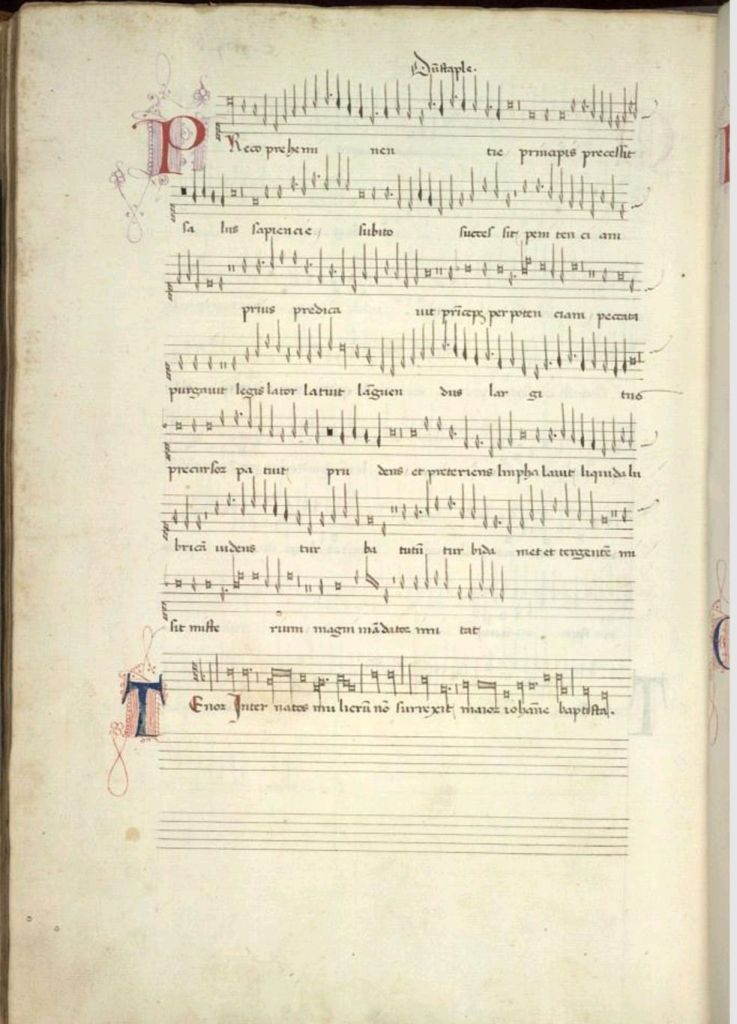

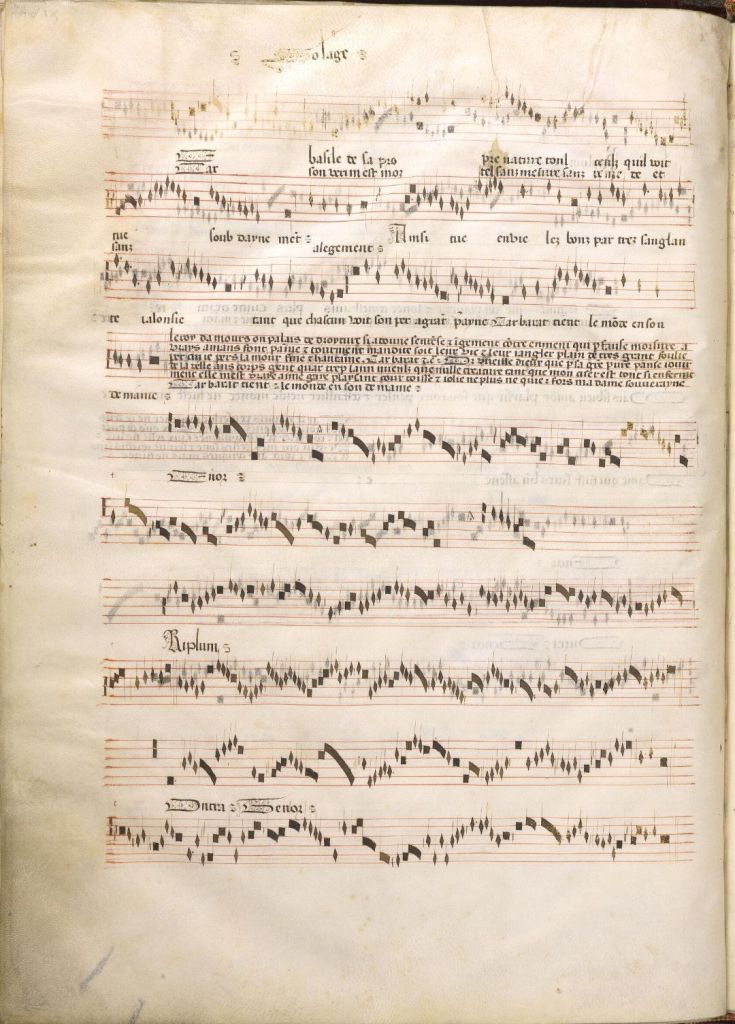

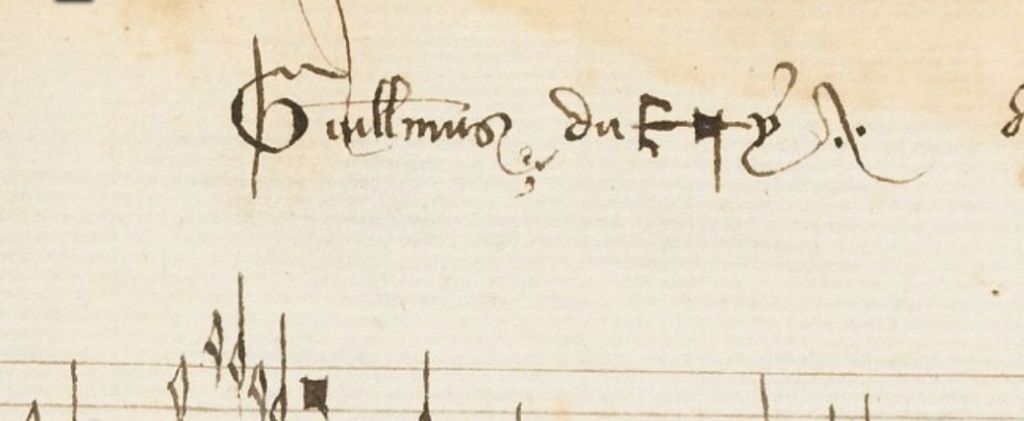

In the paintings we often see two people with ‘a text’ or ‘names’ and two other people without names, unknown, in the background, in the convex mirror or, as in the ‘Last Supper’ by Bouts, in a wooden window frame on the left (here we see two other men in the foreground above the ‘Narrative of Jesus and the Twelve Disciples’: on the left the leader of the ‘Brotherhood’ in Leuven, whose Dierik Bouts commissioned the painting, and on the right the painter D. Bouts himself. Similar to Van Eyck, who signs his own presence with the words «1434 J. Van Eyck fuit hic», or Johannes Ciconia at the end of his motet «O felix templum jubilae», and Nicolaus Zaccharie at the end of his motet «Plebs fidelis» leaves his signature musically

The two figures in the foreground could stand for the two different lyricised first lines of DuFay’s or Dunstaple’s etc. typical isorhythmic motets of this period, and the background or mirror figures for the two lower unlyricised parts. a.s.